Correct answer: c.

Discussion

When screening for novel drugs, in vitro models should always be used first. The ideal model should allow the simultaneous evaluation of a high number of compounds/potential drugs and exclusion of ineffective strategies, before their evaluation in animal models.

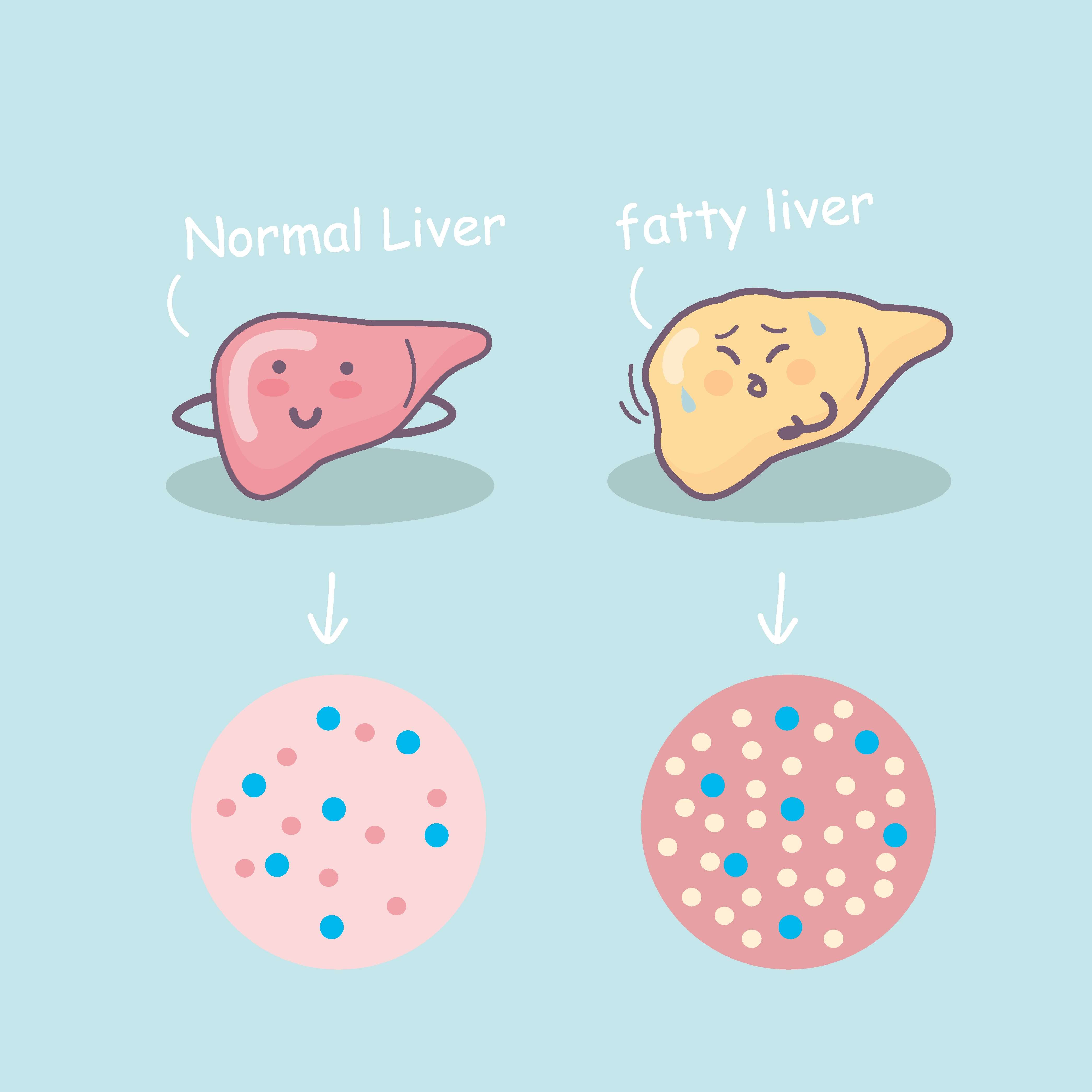

The most widely used in vitro models to evaluate fibrosis consist of cultured primary hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) that are isolated from human or animal livers and cultured in either monoculture or co-culture with other types of liver cell. Indeed, upon sustained hepatic injury, hepatocytes trigger signalling cascades that lead to activation of previously quiescent HSCs. Activated HSCs increase secretion of extracellular matrix proteins that accumulate as scar tissue within the liver parenchyma— fibrosis—and eventually lead to the development of cirrhosis.1,2 Of note, freshly isolated rodent HSCs quickly acquire the activated phenotype when plated in monolayers on regular plastic culture dishes and, as such, have long been used as in vitro models of fibrosis.3

Although they allow direct assessment of the effects of a potential drug on halting HSC activation and associated inflammatory and fibrogenic responses, HSC monolayer cultures fail to consider the hepatocyte damage-dependent activation of HSCs or even the crosstalk with additional cell types. In fact, many studies have shown that HSC and hepatocyte co-cultures prevent ‘spontaneous’ HSC activation and maintain hepatocyte functionality.4 More recently, and in order to achieve a more physiological environment, several matrices and 3-D cultures have been developed. In this regard, Leite and co-workers have developed a novel 3-D human co-culture model that maintains both hepatocyte functionality and HSC quiescence for at least 21 days.5 While primarily aimed at hepatotoxicity testing, as well as drug-induced and hepatocyte-dependent HSC activation and fibrosis, it would be interesting to see the refinement of this model to test for compounds with the potential to prevent or reverse fibrosis, as these hepatic organoids represent a substantial improvement when screening for liver fibrosis in terms of cost, animal use and translation to humans.

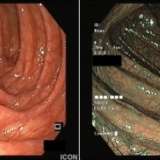

Precision-cut liver slices can also be valuable tools for the study of liver fibrosis and are considered to more closely reflect in vivo settings than cell cultures. Indeed, all liver cell types are present in these systems, namely myofibroblasts, portal fibroblasts, second-layer cells and bone-marrow-derived myofibroblasts, thus reproducing the overall cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix interactions. van de Bovenkamp and co-workers were among the first to demonstrate that culturing of human liver slices induces fibrogenesis after prolonged incubation, probably due to activation of HSCs and resident liver fibroblasts.6 Other studies have used carbon tetrachloride (CCL4) as an inducer of liver fibrosis in liver slices. However, CCL4 is a nonphysiological stimulus and has no aetiological significance in human pathology. Sadasivan and co-workers have recently developed a system in which physiologically relevant stimuli are able to induce fibrosis associated with steatohepatitis in liver slices. Indeed, the model encompasses several aspects of the fibrosis process, including steatosis, inflammation, HSC activation and extracellular matrix accumulation. This experimental platform may therefore represent a more complete method to test for the effects of potential antifibrotic drugs in vitro.

After an initial screen in vitro, the most promising antifibrotic drug should be chosen for evaluation in a relevant animal model of the disease. However, while several animal models have been developed to mimic the pathophysiology, morphological findings, biochemical changes and clinical features of human NAFLD, no single model system yet completely recapitulates the entire disease spectrum. Current animal models may be classified as genetic, nutritional or a combination of both. 4,7–10

The genetic models almost exclusively reflect the biochemical alterations found in human NAFLD, with the addition of modified diets often required to induce morphological changes. This is the case for the ob/ob genetic NAFLD mouse model. ob/ob mice have a spontaneous mutation in the leptin gene, which renders them inactive, hyperphagic and extremely obese. They also have an altered metabolic profile, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. However, these mice are also protected from liver fibrosis and, as such, progression to NASH does not occur without additional secondary stimuli, such as the use of special diets. Even so, the fibrosis that develops is only mild.

Similarly, mice are relatively resistant to HFD-induced liver injury. Most strains develop solely mild hepatic inflammation and very little liver fibrosis unless they are exposed to the HFD for a long time. For example, C57BL/6J mice fed a HFD develop many of the biochemical parameters of NAFLD, but a slight increase in perivenular fibrosis is only observed after 50 weeks on the HFD.11 By contrast, mice fed an MCD diet exhibit aggressive and early-onset NASH and fibrosis, mechanistically linked to oxidative stress. In addition, several findings suggest that MCD diet-induced fibrosis is only somewhat reversible, similar to what is observed in human NASH. Finally, MCD diet models are also more reproducible and require shorter durations of feeding to induce NASH and fibrosis, in comparison with HFD models. However, mice fed an MCD diet have very discrepant metabolic profiles in comparison with human NASH patients, namely reduced levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, insulin and glucose.

While the ability to study individual phenotypic aspects of the disease through the use of distinct models might prove valuable, model selection should be oriented with the the study purpose in mind, factoring in its advantages and disadvantages. Some models will more successfully model the physiology of liver steatosis in the context of the metabolic syndrome, while others more effectively recapitulate hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. In the end, a combination of different models might be the best strategy.

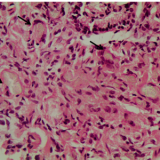

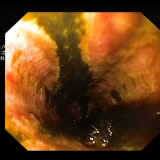

Last but not least, although human NASH liver biopsy samples are an irreplaceable and valuable tool for studying the pathophysiological events associated with the development of fibrosis, they offer few insights when the goal is to test novel drugs aimed at reversing fibrosis.

Please log in with your myUEG account to post comments.