Correct answer: c.

Discussion

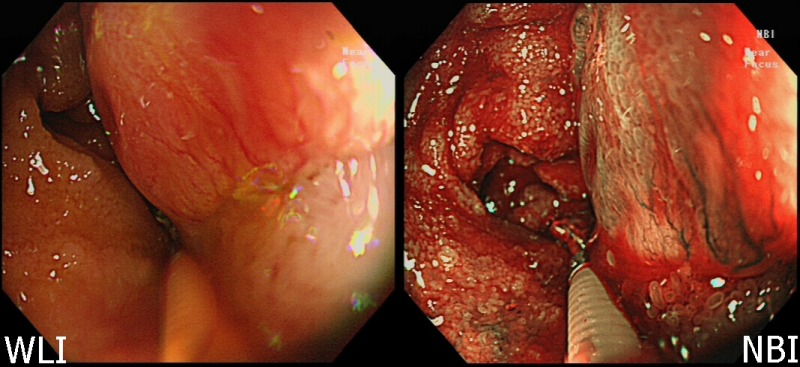

This is an odd-looking polyp that has a smooth head with some linear vessels extending from its base towards its apex. There appears to be a submucosal component to the polyp as demonstrated by the biopsy forceps in the white-light image (figure 1 [WLI]). The endoscopic diagnosis was of a neuroendocrine tumour (NET), so the lesion was sampled and an abdominal CT requested. The CT scan demonstrated a nodular mass in the terminal ileum (figure 2) and enhancing mesenteric nodal disease (figure 3).

At endoscopy, NETs (previously known as carcinoids) are firm, submucosal nodules with or without an umbilicus. The finding of thicker than usual vessels extending from the base of the polyp towards the apex is a common (but not invariable) pointer to the diagnosis.

NETs are neoplasms of the neuroendocrine cells, which are cells widely distributed throughout the body. Although the small intestine is a common site for NETs (16–29% of lesions develop at this site), the absolute incidence is low, approximately 0.5 per 100,000 per year.1 Well-differentiated lesions are usually indolent and slow growing with a prolonged natural history. By contrast, poorly differentiated lesions have a rapidly progressive clinical course and poor prognosis. The average 5-year survival rate for patients with mid-gut NETs is improving and is currently around 75%.2

Once an NET is suspected, the case should be discussed at a dedicated cancer meeting. The patient should have baseline investigations including measurement of chromogranin A (CgA) and urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) concentrations. Care needs to be taken when interpreting CgA measurements as a raised CgA concentration can have several other causes, such as use of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), atrophic gastritis, chronic renal failure, liver cirrhosis, congestive heart disease and other secretory tumours (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma, thyroid cancer). Most NETs (between 50–75%) are nonfunctional and do not secrete hormones such as serotonin, insulin or gastrin.

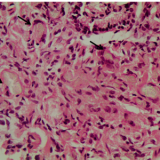

Naturally, histological analysis is essential. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies all gastroenteropancreatic NETs into low grade (Ki-67 at 2%, mitotic count <2/HPF), intermediate grade (Ki-67 3–20%, mitotic count 2–20/10 HPF), and high grade (Ki-67 >20%, mitotic count >20%).3 The prognosis is worse for patients who have NETs with a higher WHO grading and in those who have metastatic disease. Interestingly, the presence of hormone secretion is not known to influence prognosis.

In view of their high malignant potential, all ileal NETs, even those that are small, should be considered for curative surgery. Indeed, ileal NETs should not be resected endoscopically. In the 35,618 NETs registered in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Programme, local nodal involvement was found in 41% of cases and distant metastases in 30%.1 In up to 40% of cases multiple tumours were found. Owing to the known increased risk of cholelithiasis, some centres advocate prophylactic cholecystectomy at the time of surgical resection.

Following surgical resection, the European guidelines suggest post-operative surveillance every 6–12 months, via the comparison of CgA and urinary 5-HIAA levels with baseline measurements, because NETs have a relatively high risk of recurrence.4 For patients with unresectable disease, options to control tumour growth and symptoms related to tumour bulk or hormonal hypersecretion include somatostatin analogues, nonsurgical liver-directed therapy, and systemic chemotherapy. Palliative surgery should be considered for patients who are at risk of bowel obstruction.5

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroenteropancreatic NET have been published by the European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS),4 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the North American Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (NANETS).6

Please log in with your myUEG account to post comments.