Raoul I Furlano is Head of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition, University Children’s Hospital Basel, Switzerland.

Jorge Amil-Dias is a Pediatric Gastroenterologist at Hospital Lusiadas, Porto; Retired from Centro Hospitalar Universitário. S. João, Porto, Portugal.

Lissy de Ridder is at the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Erasmus MC/Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Christos Tzivinikos is Head of Paediatric Gastroenterology Department Al Jalila Children’s Specialty Hospital, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Incidents involving ingestion of foreign bodies and food bolus impactions are relatively common, primarily in paediatric populations, with a notable peak between the ages of 6 months and 6 years.1, 2 Unfortunately, there are no international European studies on the incidence of foreign body ingestion in children. Only a few retrospective survey studies exist on button battery (BB) ingestion.

Labadie et al. documented all instances of BB ingestion in France from 1 January 1999 to 30 June 2015. They revealed an average incidence of 266 ± 98.5 cases per year, with most patients under 5 years old (65.55%). Within this age group, the median age was 1.91 years with a roughly equal sex split (2105 (52.2%) males and 1877 (46.6%) females).3

A retrospective nationwide survey of paediatric gastroenterologists and paediatric surgeons in Germany between 2011 and 2016, identified 116 cases of BBs located in the oesophagus. This corresponds to 0.1 cases per million people. Children aged 8–12 months accounted for 18 cases (15%), those aged 13–24 months composed 41 cases (35%), the 25–36 months group constituted 15 cases (13%) and there were 10 cases in children older than 36 months (9%). The exact ages of the remaining 32 patients were not specified (28%). BB ingestion was most frequent between 13 and 24 months of age. Oesophageal location led to severe complications in 47 children, and 5 of these children died as a result.4

Pre-endoscopic studies have demonstrated that in approximately 80% of cases, foreign objects pass naturally through the digestive tract without medical intervention.1 The mortality rates associated with these incidents have been remarkably low. A study by Cheng et al. showed only a single fatality among 1265 children: an 8-year-old girl who was intellectually disabled ingested a chicken bone that became lodged in her oesophagus. The bone's presence resulted in erosion of the oesophageal tissue, leading to left pleural empyema and the formation of a fistula connecting the oesophagus to the left main bronchus. After removal of the foreign body she died of systemic sepsis.2 A fatality of a 2-year-old boy, reported as a case report, occurred as a result of the formation of an aorto-oesophageal conduit induced by the impaction of a sharp foreign body in the oesophagus.5

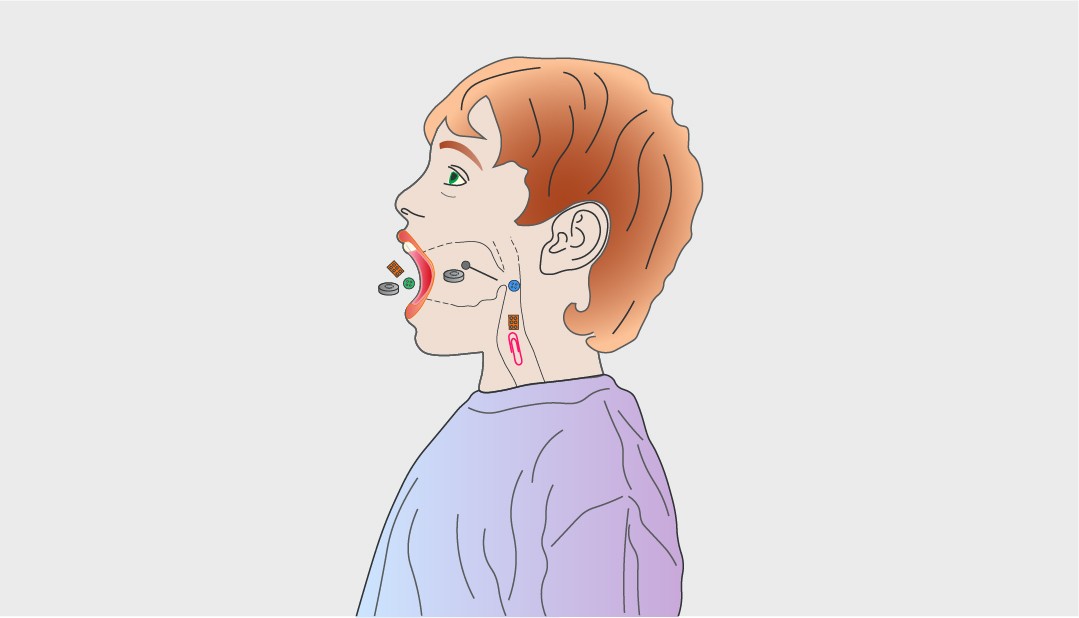

Managing a child who has ingested a foreign object poses a considerable challenge for the medical team. Several factors come into play when considering whether and when to intervene, such as the patient's age and size; the ingested item’s size, nature and location within the gastrointestinal tract; clinical symptoms; and the time since ingestion. Handling ingested blunt and sharp foreign bodies can be a delicate and potentially hazardous procedure. Here, we highlight common errors and potential issues.

@UEG 2024 Furlano, Amil-Dias, De Ridder and Tzivinikos

Cite this article as: Furlano RI, Amil-Dias J, De Ridder L and Tzivinikos C. Mistakes in paediatric foreign body ingestion and how to avoid them. UEG Education 2024; 24: 1-7.

Ilustrations: J. Shadwell.

Correspondence to: [email protected]

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Published online: February 8, 2024.

One of the most common errors with ingested foreign bodies is incorrect diagnosis. Patients or caregivers may not recollect ingestion or the object may not manifest in initial radiological imaging studies, causing a delay in diagnosis. For the initial diagnosis, radiographs can confirm the location, size, shape and number of ingested foreign bodies, and they can help rule out aspirated objects.1

Radiographs are effective in identifying most foreign bodies, particularly if the object is expected to be visible on X-rays. However, many foreign bodies are nonradiopaque, diminishing the reliability of radiographs.6 Common radiolucent objects include fish and chicken bones, wood, plastic and slender metal items.1, 6 For example, thin aluminium fragments, such as pull-tabs from beverage cans, are not radiopaque.7 Current guidelines recommend promptly referring patients with suspected foreign body ingestion to the emergency department for radiographic assessment, even if they are asymptomatic. Biplane radiographs of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis should be obtained as needed. In addition to locating radiopaque objects, it is important to assess the presence of free air in the mediastinal or peritoneal areas.1, 8 Routine contrast studies should be avoided in patients with suspected high-grade acute oesophageal obstruction due to the risk of aspiration. Additionally, opaque contrast agents like barium can coat the foreign body and oesophageal mucosa, which can hinder subsequent endoscopy.1 The use of Gastrografin® (amidotrizoic acid), a hypertonic non-opaque contrast agent, should be avoided as it can lead to severe chemical pneumonitis. Similarly, as it is in the case of using barium if aspirated.9

There is a lack of paediatric studies supporting the use of CT (computed tomography) scans for diagnosing foreign body ingestion. There is also insufficient evidence to justify the use of metal detectors for locating ingested coins or ultrasonography in children, although a few studies in small populations indicated some utility.10–12 MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is not beneficial in paediatrics because of the required anaesthesia and should also be avoided with ferromagnetic foreign bodies.13

Recommendations

- We propose early referral to the emergency department and X-ray evaluation for all patients with suspected foreign body ingestion, even if they are asymptomatic.

- Biplane radiographs should be taken of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis, as needed.

Electric current from BBs can hydrolyse tissue fluids and lead to hydroxide production at the negative terminal of the BB. This process causes rapid liquefaction necrosis and severe burns. For damage to occur, a BB must become lodged or impacted, allowing sufficient hydroxide to accumulate at a specific site. The combination of pressure necrosis and hydroxide can result in tissue erosion. The oesophagus is particularly vulnerable due to its weak peristalsis and three areas of narrowing: (1) the cricopharyngeal sphincter, (2) where the oesophagus is crossed by the aortic arch and (3) the lower oesophageal sphincter. If a BB becomes lodged in the oesophagus, it has the potential to erode into the aorta, trachea, lung or mediastinum. Notably, burns may persist even after BB removal; in one instance, an aorto-oesophageal fistula (AOF) was reported 27 days post-removal of the BB.14 Leakage of lithium BB contents does not pose harm.15 However, in alkaline batteries, hydroxide can leak out and be produced in the tissue, leading to tissue damage. It is important to note that BBs can cause injury without being chewed or damaged. Even ‘spent’ BBs, unable to power a gadget, retain a residual voltage that can be harmful, although new BBs pose the greatest risk.16 Chiari’s triad characterises the typical manifestation of AOF with mid-thoracic pain, sentinel arterial haemorrhage and exsanguination occurring after a symptom-free interval. In some instances, unsuspected cases may present with bright red haematemesis.17 In the United States, 70% of paediatric fatalities were associated with haematemesis or melaena in the days or hours leading to the fatal haemorrhage.18

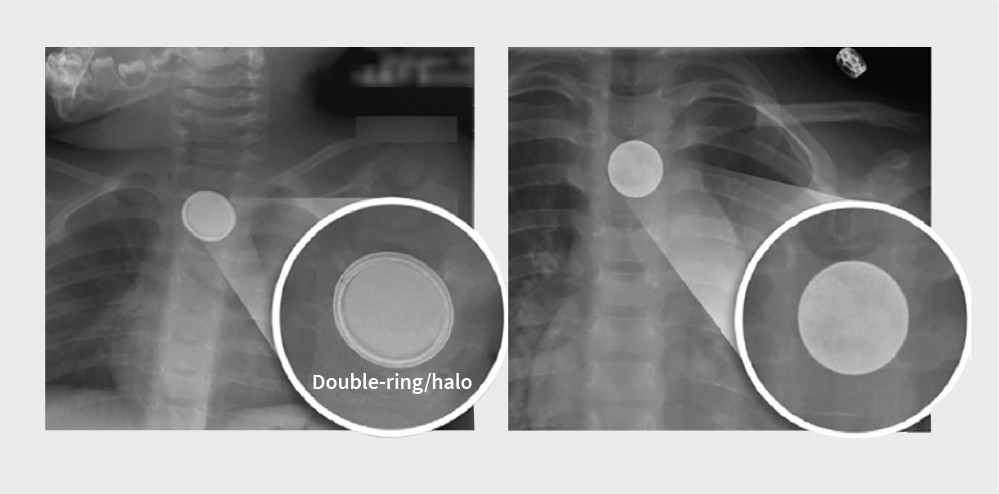

When dealing with a child who has ingested or is suspected of ingesting a coin or other blunt foreign body, radiography should be performed as mentioned above. It is essential to avoid confusing a coin with a BB. Therefore, a careful examination of the coin’s edges is necessary to exclude the double halo sign indicative of a BB (Figure 1). Lateral X-ray images can also be helpful in distinguishing between the two. However, it is important to note that in thinner batteries, the ring or halo may not be visible.19 Attempts to differentiate between a coin and a BB based on the density of a disc-shaped object have been unsuccessful.20 If the battery is lodged in the oesophagus, prompt endoscopic extraction is essential, ideally within 2 hours of ingestion. Endoscopy should not be postponed, even if the patient has recently eaten.8

Recommendations

- We suggest checking for the double halo sign on radiographs and considering lateral films to differentiate between coins and BBs.

- If the BB is in the oesophagus, prompt endoscopic removal is essential, ideally within 2 hours of ingestion. Endoscopy should not be postponed, even if the patient has consumed food.

- In cases where the BB is lodged in the oesophagus, prompt endoscopic extraction is imperative and should ideally be performed within a 2-hour timeframe following ingestion. Delays in endoscopy are strongly discouraged, even if the patient has recently consumed a meal.

Figure 1 | On radiographs, BBs have a double-ring or halo appearance (left). In contrast, coins have a homogenous appearance (right). Adapted from Sethia et al.54

In instances of oesophageal impaction due to the ingestion of BBs, the risk of severe harm is elevated, particularly in children under the age of 5 years and when the BB exceeds a diameter of 20 mm.16 Various strategies for reducing injuries have emerged in recent years. If the patient’s condition is stable and ingestion occurred within the past 12 hours, it is advisable to consider administering honey (for individuals over 1 year of age) or sucralfate (1 g/10 mL suspension) while awaiting endoscopy.21 However, it is crucial to emphasise that this should never impede the prompt performance of an endoscopy.22 The recommended dosage for both substances is 10 mL (equivalent to 2 teaspoons) every 10 min, with a maximum of six doses for honey and three doses for sucralfate.21, 23 It is imperative to avoid cathartics and refrain from inducing vomiting. These measures are by no means a substitute for the urgent removal of the BB through endoscopy, ideally within 2 hours of ingestion. If ingestion extends beyond 12 hours, a CT scan and consultation with a surgeon should precede endoscopic removal.

During the removal procedure — be prepared for immediate complications, such as oesophageal perforation and tracheo-oesophageal fistula, and assess the risk of injury based on the proximity to significant vascular structures, including arterial fistulas.16, 24 If no visible oesophageal perforation or fistula is detected, conduct endoscopic irrigation of the injured tissue site using 50–150 mL of a sterile acetic acid solution (0.25%) while simultaneously removing any excess irrigation by suction.21 If there is evidence of perforation, fistula or severe circumferential injury, consider inserting a nasogastric tube (NGT) while in the operating room with a direct endoscopic view. Do not blindly insert an NGT or do so on the ward. In cases of oesophageal BB ingestion, tissue injury can progress and complications such as bleeding from a vascular fistula can occur up to 3 weeks after ingestion.14 Therefore, if severe mucosal injury is apparent upon removal, it is advisable to order contrast imaging (MRI, CT angiography) to assess the proximity of the oesophageal mucosal injury site to major blood vessels, particularly the aorta.25 Consider performing an oesophagogram before commencing a clear liquid diet. If this diet is well tolerated, gradual progression to soft or mashed foods is recommended, usually for a period of up to 4 weeks while administering acid-blocking medications.

Maintain vigilance for potential delayed complications, which can manifest over several weeks: oesophageal perforation, tracheo-oesophageal fistula, AOF, vocal cord paresis or paralysis, mediastinitis, spondylodiscitis or oesophageal stricture. Comprehensive discharge instructions must be provided, with a strong emphasis on recognising the signs and symptoms of these potentially delayed complications, particularly upper gastrointestinal bleeding arising from a vascular fistula. A concise overview of the diagnosis and management of BB ingestion cases in children can be found in a position paper from the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) (Figure 2).24

Figure 2 | Diagnosis and management of BB ingestion. Adapted from Mubarak A, Benninga MA, Broekaert I et al.55

Once a foreign body is suspected or confirmed, the timing of intervention can be critical. Some objects may pass through the digestive tract without causing harm, while others may become lodged or cause damage relatively quickly. Delaying intervention can lead to complications. The timing of endoscopy depends on various factors, including the patient’s age and clinical condition, time of last oral intake, type of ingestion, location of object in the gastrointestinal tract and time since ingestion. Additionally, judgment of the risks of aspiration, obstruction or perforation should guide the timing of endoscopy. In broad terms, the timing can be classified as emergent (within 2 hours of presentation, irrespective of nil by mouth status), urgent (within 24 hours of presentation) or elective (more than 24 hours after presentation).8 Most clinically stable patients without symptoms of high-grade gastrointestinal obstruction do not require urgent endoscopy because the ingested object will usually pass spontaneously, except in the case of BB ingestion.1, 26, 27 However, children with oesophageal foreign bodies or food impactions, even when asymptomatic, should undergo urgent removal (within 24 hours of presentation) because delayed removal reduces the likelihood of success and increases the risk of complications, including perforation.

These recommendations are based on studies involving adults due to a lack of paediatric research.28, 29 Furthermore, in the case of food impaction, one must always consider the possibility of eosinophilic oesophagitis as the cause and exclude it through biopsies, preferably not at the site of the bolus impaction but above and below it. However, a recent study showed that food bolus impaction due to eosinophilic oesophagitis was significantly more common among adults than children.30 For foreign bodies in the stomach with no risk of anatomical complications in the digestive segments beyond the stomach, most foreign bodies usually pass within 4 to 6 days.

Therefore, conservative outpatient management is suitable for most asymptomatic gastric foreign bodies, except for BBs.2, 22, 31, 32 However, Lee reported removal within 24 hours in cases where the ingested foreign bodies were unlikely to pass through the pylorus (longer than 6 cm or more than 2.5 cm in diameter).33 If a child with foreign body ingestion is managed as an outpatient, they should maintain a regular diet and their parents should monitor stools for evidence of object passage. Small, blunt objects, including coins, may take as long as 5 weeks to pass spontaneously.26, 31 A major exception to this approach to gastric foreign body, would be the presence of more than one magnet in the stomach or duodenum (see Mistake 6).

Recommendations

- We suggest blunt foreign bodies, coins or impacted food in the oesophagus should be removed urgently in asymptomatic children (within 24 hours). If the child is symptomatic, emergent removal (within 2 hours) is indicated.

- Removal of blunt foreign bodies from the stomach or duodenum should be considered if the child is symptomatic or if the object is large (greater than 2.5 cm) or long (more than 6 cm). Otherwise, blunt foreign bodies in the stomach should be monitored and retrieved only if they cause symptoms or fail to pass spontaneously after 4 weeks.

The frequency and nature of ingested sharp objects are strongly influenced by cultural and environmental factors. In Asian and Mediterranean families, where fish is a staple introduced early in life, instances of young children ingesting fish bones are more prevalent.27 Symptoms commonly arise if the foreign body is lodged in the upper-mid oesophagus, leading to pain, dysphagia, odynophagia and drooling. Despite this, a significant proportion of patients may remain asymptomatic for weeks, with potential complications such as delayed intestinal perforation, extraluminal migration, abscess formation, peritonitis, fistula formation, appendicitis and penetration of organs like the liver, bladder, heart, lungs and even rupture of the common carotid artery.34–41 The ileocecal region is the most frequently affected site for intestinal perforation, although instances have been documented in the oesophagus, pylorus, the junction between the first and second part of the duodenum, and the colon.42 Complication rates are higher in symptomatic patients, those with a delay in diagnosis beyond 48 hours, or those who have ingested radiolucent foreign bodies.43–45 Toothpick and bone ingestions pose a particularly high risk of perforation and are the most common types of objects requiring surgical removal.44

Evaluation of patients suspected of ingesting sharp-pointed objects is crucial to determine the object’s location. Since many sharp-pointed objects are not visible on radiographs, endoscopy should follow a radiologic examination with negative findings when there is a high suspicion. Objects lodged in the oesophagus, especially sharp-pointed ones, constitute a medical emergency due to the potential for high-risk complications like perforation and migration. Direct laryngoscopy is an option for removing objects lodged at or above the cricopharyngeus. If laryngoscopy is unsuccessful or if the object is below this area, flexible endoscopy may be performed. Sharp-pointed objects in the stomach or proximal duodenum should also be removed urgently. If these objects pass through the duodenum, enteroscopy or surgery may be considered in symptomatic patients. In asymptomatic cases where observation is chosen over immediate removal, monitoring in a hospital setting with daily abdominal X-rays may be considered.13 Patients should be instructed to promptly report symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, persistent temperature elevation, haematemesis or melaena.46 The average transit time for a foreign object ingested by children is reported as 3.6 days, while the mean time from ingestion of a sharp object to perforation is reported as 10.4 days.47, 48 Surgical removal may be considered if the foreign body has not progressed on imaging in 3 days or if the patient becomes symptomatic.47, 48

Recommendations

- In cases of ingested sharp foreign bodies, endoscopy should be performed even if the objects are not visible on radiological imaging.6

- Surgical removal of a non-progressing ingested sharp foreign body (as determined by radiological imaging) should be considered after 3 days or if the patient becomes symptomatic.

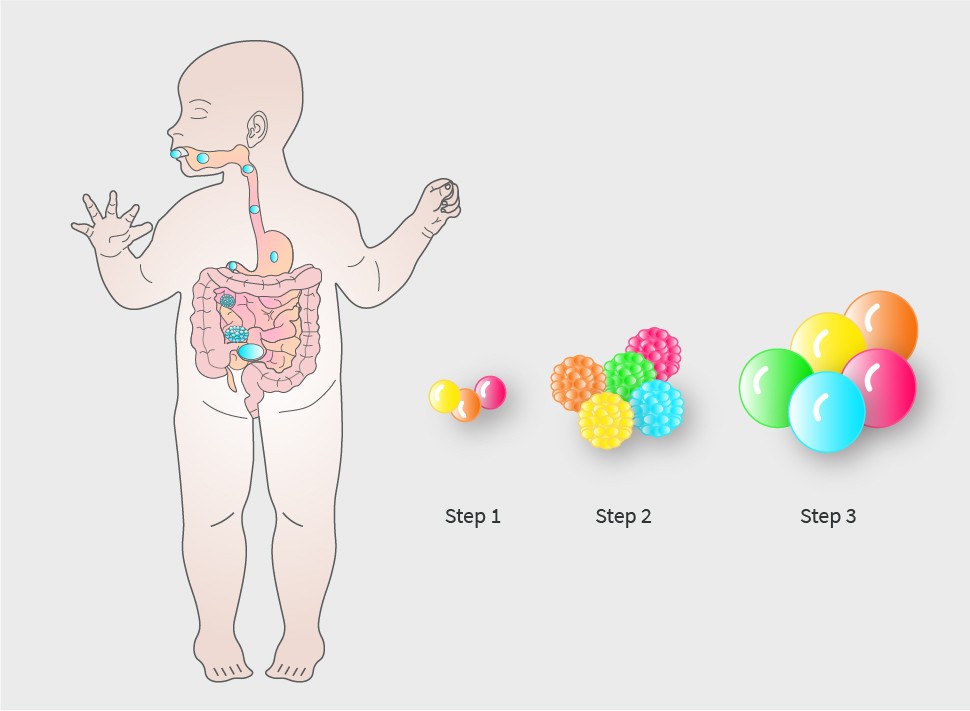

Ingestion of magnets is a unique category of foreign body ingestion associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially when multiple magnets are ingested sequentially or in conjunction with other metallic foreign bodies. Prompt recognition and endoscopic removal are necessary for neodymium magnets, which exhibit stronger magnetism, to prevent them from moving beyond the reach of a gastroscope.49 Once they move beyond this point, continuous monitoring involving a surgical team is essential, even if the patient remains asymptomatic, as magnets can exert strong attractive forces on each other through multiple layers of the bowel and gastric wall (Figure 3).

Figure 3 | Management of multiple magnets ingested in a child: a | Evaluation and management of a child with multiple magnets ingested. Adapted from Nugud et al.49 b | Magnets can strongly attract each other through multiple layers of bowel/gastric wall. Adapted from Kodituwakku et al.56

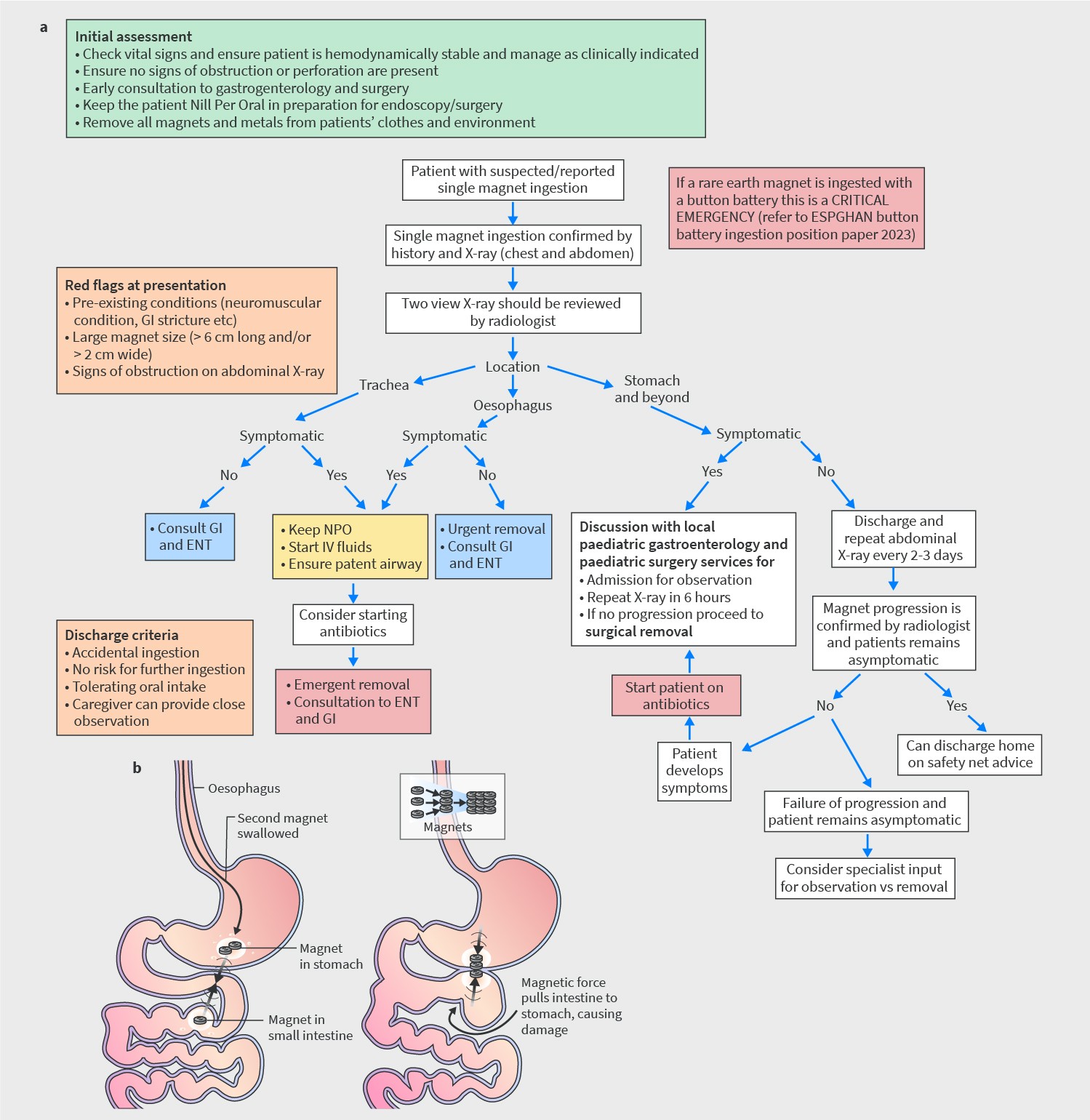

In the case of ingestion of beads or balls made of superabsorbent polymers, emergent endoscopic removal (within 2 hours) is advisable, as these can potentially lead to fatal bowel obstruction in children secondary to rapid increase in bead size within the intestinal tract (Figure 4). For patients in whom ingestion is suspected but not witnessed, the decision to proceed with endoscopy may be taken even prior to the onset of clinical symptoms, contingent upon the degree of suspicion. If upper endoscopy fails to identify the object, distal bowel obstruction should be avoided by close monitoring with the involvement of a surgical team.34

Recommendations

- We suggest in cases of ingestion of multiple magnets, especially neodymium magnets, early recognition and endoscopic removal are essential. Continuous monitoring is necessary if the magnets move beyond the reach of a gastroscope.

- In cases of suspected ingestion of superabsorbent polymer beads, emergent endoscopic removal (within 2 hours) is advised to prevent potential bowel obstruction. Continuous vigilance and surgical consultation are necessary if the object is not initially identified with an upper endoscopy.

Figure 4 | Proposed mechanism of superabsorbent polymer bead-induced bowel obstruction in children. Adapted from W. Care et al.57

In regions with high drug trafficking, the practice of ‘body packing’ can also involve children and teenagers. Illegal drugs are concealed in latex condoms, balloons or plastic and swallowed for transportation.50, 51 If there is a risk of leakage or rupture of these packets, endoscopic removal should not be attempted. Surgical intervention is necessary when the packets do not progress or when signs of intestinal obstruction are present. In cases where packet rupture is suspected, surgery and urgent medical assessments for drug toxicity are warranted.8

Recommendation

- Endoscopic removal of packets containing drugs ingested by children and teenagers should not be performed.

Both rigid and flexible endoscopic approaches seem to demonstrate comparable safety and efficacy in the extraction of oesophageal foreign bodies. However, the use of flexible endoscopy for oesophageal foreign body removal requires significantly less time than rigid endoscopy. Flexible endoscopy is likely to enable a more comprehensive examination, including the possibility of obtaining biopsies of the oesophageal mucosa, in comparison to rigid endoscopy.52 One study has indicated that rigid oesophagoscopy carries a higher complication rate when used for oesophageal foreign body extraction. Complications in the study of Berggreen et al. included two cases of post-procedure fever and two cases of extended respiratory depression. Therefore, it should be reserved for proximally located blunt objects, and its routine use is discouraged.53

Recommendation

- Rigid oesophagoscopy should not be used routinely for oesophageal foreign body retrieval in children.

-

About the authors

-

Your paediatric foreign body ingestion briefing

UEG Week

- ‘European society of paediatric gastroenterology hepatology and nutrition (ESPGHAN) button battery ingestion taskforce survey across Europe and beyond – iceberg below the surface.’ – poster at ueg week 2023.

- ‘A UK based retrospective analysis of the management of patients presenting as an emergency with foreign body in the oesophagus.’ – Poster at UEG week 2023.

- ‘Foreign body removal and bougienage.’ – Session at UEG Week 2023.

Standards and Guidelines

- Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, Häfner M, Hartmann D, Hassan C, et al. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2016 ; 48 (5): 489–496.

- Thomson M, Tringali A, Dumonceau JM, Tavares M, Tabbers MM, Furlano R, et al. Paediatric Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017; 6 (1): 133–153.

- Nugud AA, Tzivinikos C, Assa A, Borrelli O, Broekaert I, Martin-de-Carpi J, et al. Pediatric Magnet Ingestion, Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention: A European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Position Paper. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2023;76 (4): 523–532.

- Mubarak A, Benninga MA, Broekaert I, Dolinsek J, Homan M, Mas E, et al. Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Button Battery Ingestion in Childhood: A European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition Position Paper. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2021 ;73 (1): 129–136.

Please log in with your myUEG account to post comments.