Young GI Blog

Clinical Trials 101: Unpacking the Fundamentals - Part 2

June 19, 2023 | Giovanni Marchegiani, Coskun Ozer Demirtas, Maarten te Groen

The Design, Implementation, and Execution of Clinical Trials

What are the different types of clinical trial designs?

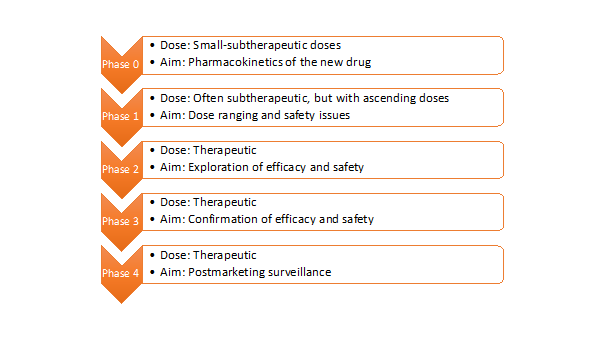

Before starting to design a clinical trial, you must first assess the preferred characteristics of it. One can describe a clinical trial design according to the presence of a control group as a comparator to an investigational group (uncontrolled or controlled trials), the methodology used to distribute the participants to a treatment or control group (randomized or non-randomized trials) and the awareness of the researchers or participants on which group they will be allocated to (open-label or blind trials). Keeping this in mind, the randomized, controlled, blinded designs minimize the risk of error and bias and provide higher validity, credibility, and reliability to the clinical trial. A clinical trial can further be categorized according to the significance of the estimated results to be found between groups (superiority or bioequivalence or non-inferiority trials), or the structure of the proposed treatment (parallel or cross-over or sequential trials). Unlike the traditional fixed sample designs, a clinical trial can also be prospectively planned for modifications at certain points based on the accumulating data from the subjects, which is called ‘’adaptive design’’. It is suggested to identify the type of the clinical trial design not only in the research protocol, but also in the final report. For clinical drug/intervention development trials, one should also specify the phase of the study. They often consist of five phases and each phase builds on the results of previous phases (Figure 1)1.

What are the issues when designing a clinical trial?

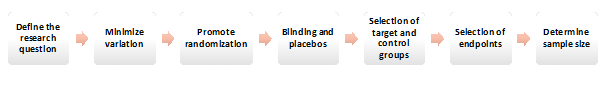

Several fundamental factors must be considered when designing a clinical trial (Figure 2). Every clinical trial design begins with a clearly defined research question. This question transforms into a testable and measurable hypothesis over time. After the borders of the correct question and hypothesis are drawn, the aim is to minimize the variation often reached by determining consistent endpoints and using standardized methods for quantifying parameters. To reduce the risk of bias and provide the balance regarding potential confounding variables, accurate randomization is essential. Providing a placebo arm and blinding also prevents biases and behavioral changes during the study, although such design features are typically limited to drug development trials. The investigators also must consider the intended target to use the analyzed intervention/drug. The control groups can be selected in various ways, that can be either placebo, no treatment, active treatment, dose comparison concurrent controls or historical controls2. Another important issue for clinical trial design is to decide on optimal endpoints. The endpoint of a trial is often aimed to be rationale, practical, reachable, interpretable, and ideally affordable. Determination of a statistically supported sample size that is ideal to draw conclusive results is another necessity when designing a clinical trial3. Final step is to prepare a research protocol to serve as a roadmap to be followed during the study period.

How to implement your trial?

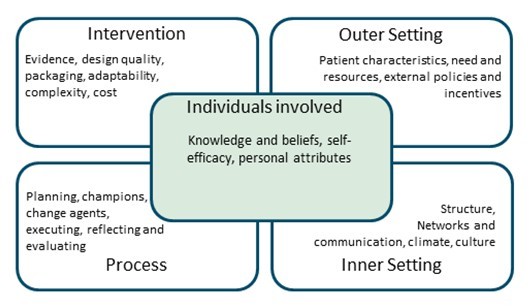

Once the research protocol has been prepared, the implementation phase begins. It is time to broaden your scope and evaluate the factors that make your trial successful. The methodologically most sound study design is often not the best one in terms of successful execution and completion. It can be helpful to use a structural framework for implementation assessment. There are frameworks assessing trial success from an outcomes and determinant perspective, respectively. Both aim at providing a realistic view of your plan and preventing unnecessary pitfalls. Proctor and colleagues’ implementation framework employs eight implementation outcomes including feasibility, adoption and acceptability of a trial in clinical practice4. These factors can be personalized for your trial to define planned success outcomes. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) aids in the identification of determinants of trial success5. This framework divides determinants into intervention characteristics (figure 3). Once barriers to trial success are identified, strategies for improvement can be implemented. For complex problems, the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) may be used to aid strategy development6. If done right, a critical appraisal of trial success saves you time and resources during the execution phase.

How to execute your trial?

After the draft has been optimized, the final version should be sent to the medical ethical committee, and if applicable, drug registration committee or other (inter)national regulatory agency. This process could take multiple weeks to months before definitive approval is granted. In the meantime, you can prepare for efficient trial execution. These may include development of case report forms, visits to collaborating centers and subsequent training of collaborators. Electronic data capturing systems offer tailor-made case report forms, audit trails, monitoring and adverse event registration although it depends on the financial landscape if these systems are available. Training material may consist of (oral) presentations, online courses and hand-outs with information for use in clinical practice.

After approval of the trial protocol, it remains important to screen for any barriers that may impede efficiency and quality during the execution phase. Especially in the beginning of the inclusion period, you should keep an eye out for arising problems, including trends in missing data or protocol violations. Sharing trial progression, for example through digital newsletters can help motivate other participating centers and ensure optimal inclusion speed. If you have reached the inclusion target it is recommended to double-check any missed drop-outs before closing your trial. And voila, your data is (should be) there!

-

References

2. Nair B. Clinical Trial Designs. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019 Mar-Apr;10(2):193-201. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_475_18. PMID: 30984604; PMCID: PMC6434767.

3. Evans SR. Fundamentals of clinical trial design. J Exp Stroke Transl Med. 2010 Jan 1;3(1):19-27. doi: 10.6030/1939-067x-3.1.19. PMID: 21533012; PMCID: PMC3083073.

4. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011 Mar;38(2):65-76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. PMID: 20957426; PMCID: PMC3068522.

5. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009 Aug 7;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. PMID: 19664226; PMCID: PMC2736161.

6. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015 Feb 12;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. PMID: 25889199; PMCID: PMC4328074.

Please log in with your myUEG account to post comments.