Correct answer: d.

Discussion

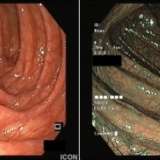

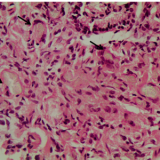

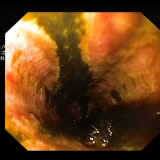

This situation is a frequent conundrum in clinical practise. Of course, such cases should be discussed in your local cancer meeting. Poor healing appears to be more frequent in the elderly, those who have significant comorbidities and with certain drug treatments, such as NSAIDs, potassium chloride, bisphosphonates, doxycycline or nicorandil. Chronic gastric ulceration has also been reported secondary to nearby infiltrating adenocarcinoma, lymphoma or stromal tumours, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and lymphoma.

A paper from the H2-receptor era reported on the outcomes of 129 ‘giant gastric ulcers’ (defined in this study as ulcers large enough to occupy at least one wall of the stomach).1 Compared with patients who had smaller gastric ulcers (presumably occupying less than a gastric wall), patients who had giant gastric ulcers were significantly older (p< 0.05), had more aggressive disease with a higher risk of bleeding, and presented more frequently with anorexia and weight loss. In this study, the most common location for a giant gastric ulcer was the gastric body.

The healing rate at 12 weeks was 88% for patients on cimetidine. Patients not offered maintenance therapy with cimetidine had a 50% risk of ulcer recurrence. Only two of the giant gastric ulcers identified finally proved to be malignant. Interestingly, a second review reported a similar ‘refractory gastric ulcer’ rate of 17% (that is, ulcers not healed after 8 weeks of treatment) even though ulcers were treated with full-dose lansoprazole.2 There was no difference in the healing rate between patients randomly allocated to receive 30 mg or 60 mg of lansoprazole.

As giant refractory gastric ulcers are far more likely to be benign than malignant, performing a gastrectomy would be premature in this case. Nevertheless, the report of atypia and the presence of a couple of small nodes nearby should not be ignored in a patient who would be a candidate for gastrectomy if cancer is ultimately confirmed. EUS with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the nodes would be reasonable but would of course only be of use in the unlikely event that the histology confirmed cancer.

The main choice now lies between taking another set of biopsy samples, perhaps using ‘jumbo biopsy forceps,’ or organising a laparoscopy with a gastric wedge biopsy. As I have seen several endoscopy-and-biopsy-negative cancers correctly identified by laparoscopy with a gastric wedge biopsy, I believe that this would be the best way forward for this patient. Even if a wedge biopsy conclusively rules cancer out, there is a risk of ulcer complications such as bleeding (12–44%) and perforation (1–2%).3 For this reason, a proportion of benign giant ulcers may ultimately be managed with a partial gastrectomy; however, perioperative mortality may be high with emergency surgery in an elderly patient.4,5,6

Please log in with your myUEG account to post comments.